Two different sources, one a newspaper and the other a magazine on the scrapping of the

USS Patterson. I have transcribed them from the originals.

Newspaper clipping October 22, 1946 (newspaper name

unknown).

From the collection of Robert A. Coburn, Sr., Storekeeper 2/C 1944-1946.

GLUM CREW WORKS

ON ‘CAN’ FOR JUNK

Destroyer Patterson, With 17 Battle Stars,

Seen Making ‘Good Razor Blades’

While awed thousands boarded the big carriers and the newer destroyers in New York

Harbor yesterday, admiring their spit and polish, the crew of the destroyer Patterson

worked glumly in the rain, dismantling their ship for its graveyard run. It is to be

decommissioned within a forthnight.

Breaking up a fighting "tin can" that had battered its way

from Pearl Harbor to Okinawa to earn seventeen battlestars – fourteen in the

Asiatic-Pacific theatre, two in the Philippine Liberation, one at Pearl Harbor – was a bitter task for the handful of old-timers in her crew of 250 officers and

men.

Down in the CPO’s foc’sle five old hands talked about

it—Chief Fire Control Man Stanley A. Hatlestad of Frost, Minn; Chief

Electrician’s Mate Henry Swires of Brockway, Pa.; Chief Water Tender Raymond J. J.

Russell of Union City, Tenn; Chief Torpedoman R. E. Wickland of Sheldon, Wis., and

Soundman First Class Fred Rankin of Ennis, Mont.

They talked of the morning of Dec. 7 when, lying alongside the Henley

and the Talbot, the Patterson rocked under the Japanese Pearl Harbor attack in Berth X-11,

between Pearl City and Aiea Landing.

Chief Hatlestak recalled how "the Japs strafed our whaleboats after

their bombs had rocked us, especially one that fell off the port bow." Twenty men

were on the beach that morning, but the others jumped to the guns and their .50-caliber

machine guns got one Japanese plane, and their 5-inch rifle got another bearing down on

the seaplane tender Curtiss.

Ships Seek Attackers

Within the hour the Patterson was under way, with the

Detroit the Phoenix and the St. Louis tearing westward after the attackers. Their skipper

Lieut. Comdr. Frank Walker, caught up to them in a whaleboat and took over from the

executive officer, Alfred White.

Two months later, off Bougainville, the Patterson had her first

casualty. She was screening carriers against surface and underwater attack, picking a

carrier pilot out of the water, when forty Japanese Bettys bore in, dropping bomb loads

everywhere. The Patterson zig-zagged until her rudder jammed. A bomb fell close and tore a

wound in Charlie Faught, ship’s cook.

The group talked at length about the Patterson’s part in the first

battle of Savo Island. Sometime after midnight on Aug. 9, 1942, Hatlestad, on watch above

the bridge, spotted an enemy task force, 4,000 yards away, bearing down. A Japanese

cruiser closed in to 1,700 yards with her searchlight on the destroyer, but Gunner’s

Mate Lawrence, on the 20-mm gun smashed the light and threw the cruiser off.

The day before, the Patterson got four kills out of twelve Japanese

planes that were shot out of the sky near Guadalcanal. On the morning of the 9th

she picked up 400 men of the Australian Royal Navy’s sinking flagship, the Canberra,

although enemy torpedoes hissed under and around her. One shell knocked out her two after

guns, but she stayed in the fight, swapping shots with the enemy.

After that she was in on most of the big sea

shows—Tulagi, the capture and defense of Guadalcanal, in the Eastern Solomons,

Eastern New Guinea, off the Solomons, at New Georgia, in the Marianas, the Western

Carolines, Leyte, Luzon, Iwo Island and finally, at Okinawa.

The men toyed with the brass plate presented to the Patterson by survivors of the

carrier Bismark Sea who fished it out of the water off Iwo Island on Feb. 21 in the

pitch dark. Lieut. J. P. Kavanagh disclosed that "our skipper (Comdr. A. H. Angelo of

Berkley, Calif.) is sending the plate to the widow of Lieut. Comdr. Walter A. Hering, who

was in command when he picked up the Bismark survivors."

Decommissioning Services

In about ten days to two weeks, when the Patterson is stripped

clean, there will be decommissioning services aboard and she will make for the Navy Yard

in Brooklyn and for the scrap heap.

Mailman Second Class John J. Butler of 196 Lawrence Avenue, Brooklyn, standing in the

heaped up fighting lights, disorderly deck crates and dismantled ships gear, said:

"Go ahead, fella, give all the publicity to the big ships. The Old Pat’s

going to be made into razor blades. But don’t forget this—there was many a tight

spot when the big ones were screaming. ‘Screen us, Old Pat, screen us: and we

screened ‘em, or they wouldn’t be all spit and polish now, with all the pretty

ladies walking their decks in New York Harbor. Don’t forget that."

Chief Russell said: "Easy, Johnny. She did her bit and we know it, and that’s

enough. And if she’s going to be turned into razor blades, she’ll make good

razor blades—the best."

The following is transcribed from a magazine article. Date and magazine unknown but was

under the ARMY & NAVY Section. It was prior to the Patterson’s final scrapping..

U. S. S. FARRAGUT, DEWEY, PATTTERSON

Next port: the bone yard

OPERATIONS

OLD PAT

When she minced into Pearl Harbor, just in time to see war break over Hawaii, the

destroyer Patterson was only four years old and one of the best. A survivor of Dec

7’s disaster, she became one of the thin line of U.S. warships left to stop the Jap

fleet in the Pacific. Lean as an alley cat, "Pat" stalked off to westward. It

was a bad time. On the blackest night in U. S. naval history, off Savo Island, the Japs

destroyed the Allied cruisers Astoria, Quincy, Vincennes and Canberra. Pat, hit and hurt,

stood by and picked up 400 survivors. It was the kind of work expected of destroyers. They

were the tin cans and expendable.

With little rest Pat labored on ,convoy-ing ships off Australia, operating in the

"Slot," seeing the tide of war turn at last as reinforcements began to arrive

from a nation which had tardily remembered its Navy. She fought at Saipan and Tinian,. She

was a picket ship. She was fire support. She was mobile 5-in. artillery steaming in- shore

against Jap pillboxes. She operated at Guam and later at Palau and later with Halsey in

the second Battle of the Philippines.

Like her sister cans, she seldom figured in communiqués, but she was beloved by the

big ships whenever there was trouble. ("Screen us, Pat!") She rescued 124 men

from the blazing Ommaney Bay. She rescued 106 survivors of the Bismarck Sea off Iwo Jima.

She fought off Okinawa. When there was nothing else to do she carried the mail.

When the war ended, rusty old Pat lay in Saipan Harbor, worn out and obsolescent. Soon

after, she was ordered home.

Last Port. In some ways, Pat had been lucky. Seventy-one of her sister destroyers had

been lost in the oceans of the world"; their bones lay in Iron Bottom Bay, in Bali

Strait, in watery locations marked simply:

"12 28 S, 164 08 E."

She plodded back across the Pacific, rested briefly at San Diego and went on the New

York Harbor. She was tucked away in an East River pier, her carcass decently out of sight.

Agents came aboard her to calculate coldly the amount of aluminum in her superstructure,

the steel in her hull. Officers and men learned the that old Pat was through. They were

not bitter. More than 200 other veterans of World War II (about 600,000 tons of warships)

were also marked for the scrap heap. Considering the life she had led, Pat had lasted a

long time.

They set to stripping her of her movable gear, littering her decks with outmoded radar,

communication equipment, boxes of crockery and silverware. A faded jack at her bow, her

commission pennant, and her ragged ensign hanging limply aft indicated that she was still

a ship of the U. S. Navy, but soon these flags would be hauled down and she would be towed

off to the bone yard.

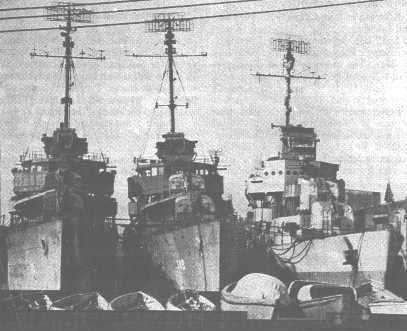

On Navy Day old Pat rested alongside her two sister who were awaiting the same forlorn

ending –the heroic Dewey and Farragut. Across Manhattan, in the North River, the

august battleships and carriers and the newer cans of the U.S. Fleet took the applause.

|